Two Brain Systems in Dynamic Interaction

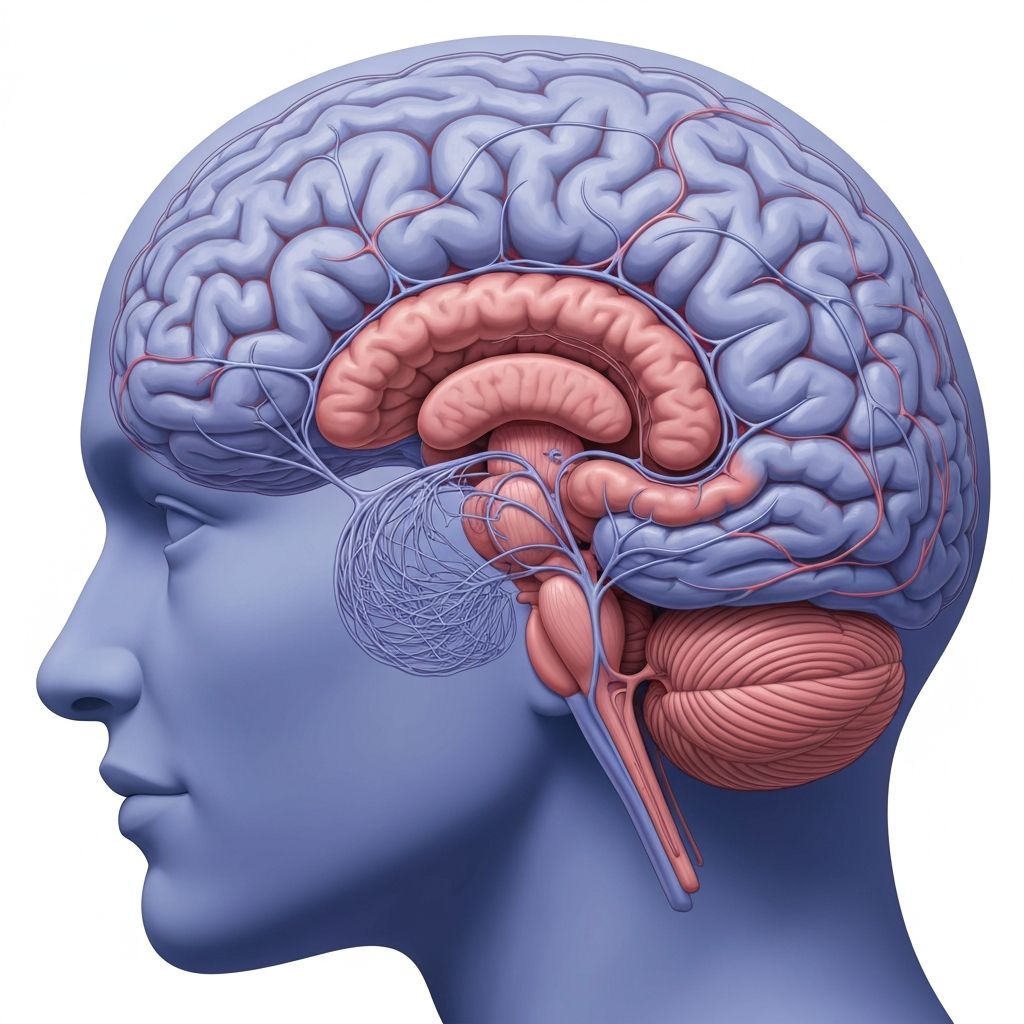

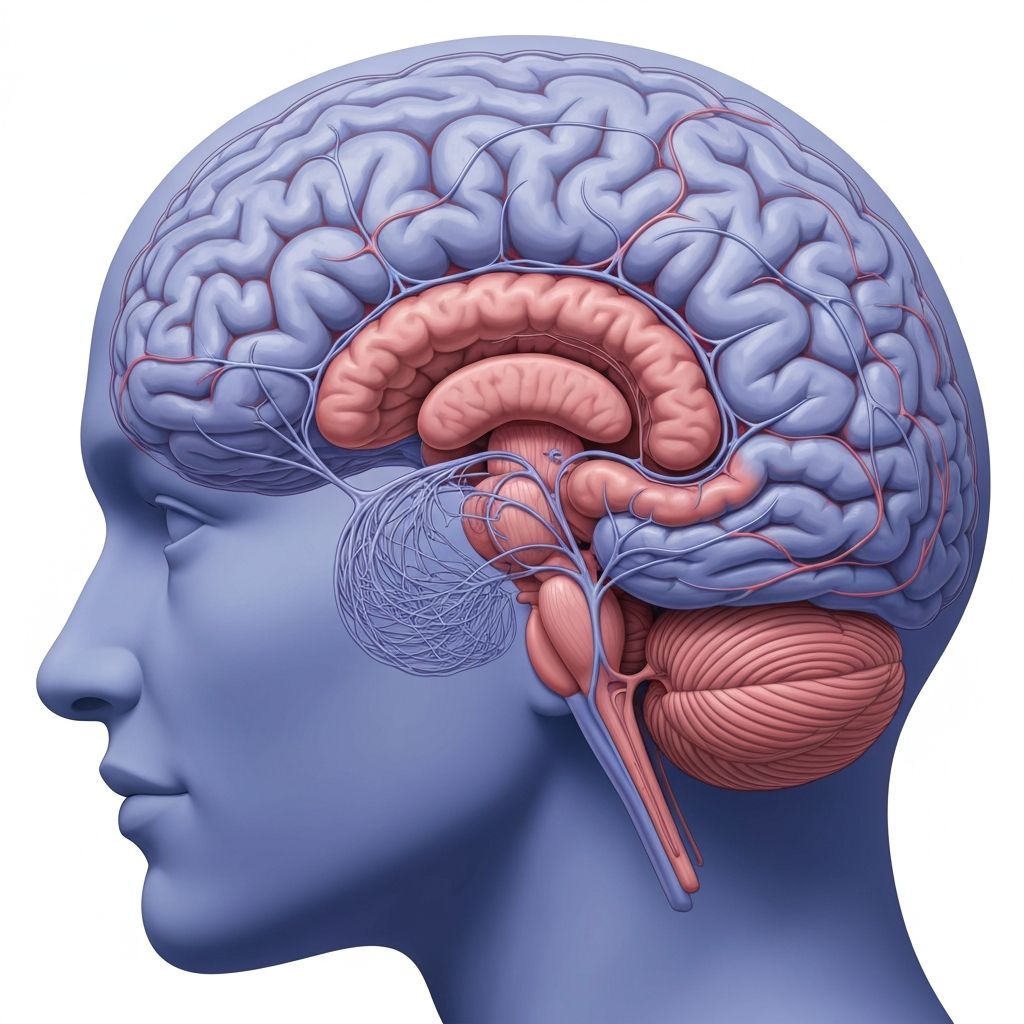

Human emotional and behavioral responses emerge from interactions between distinct brain systems. The amygdala, located deep within the temporal lobes, serves as the brain's emotional processing center, detecting emotional significance in stimuli and coordinating emotional and physiological responses. The prefrontal cortex, located in the frontal lobes, supports executive functions including deliberate decision-making, impulse control, and the regulation of emotional responses.

These two systems maintain dynamic relationships that significantly influence behavior, including eating-related decisions and responses. Understanding how these regions interact illuminates the neurobiological basis through which emotional intensity can bypass deliberate, rational decision-making around food choices.

The Amygdala: Emotional Processing Center

The amygdala continuously processes emotional significance in perceived stimuli. When the amygdala detects emotionally relevant information—threat signals, reward-related cues, or emotionally laden contexts—it coordinates appropriate emotional and physiological responses. In the context of food-related emotions, the amygdala activates in response to food-associated cues, emotional contexts associated with eating, and stimuli previously paired with emotional food consumption experiences.

Importantly, amygdala activation occurs rapidly, often before conscious awareness of stimuli. This creates a system wherein emotional responses to food cues can be triggered automatically and preconsciously. When individuals encounter foods or contexts with strong emotional associations, amygdala activation generates motivational states and physiological responses promoting eating behavior before deliberate cognition can engage.

This automatic amygdala responsiveness has evolutionary advantages—rapid emotional responses to significant stimuli can be survival-relevant. However, in contexts of intense emotional experience or chronic emotional distress, rapid amygdala activation can generate strong eating motivations that override deliberate decision-making.

Prefrontal Cortex: Deliberate Control and Regulation

The prefrontal cortex supports cognitive functions including deliberate decision-making, planning, and impulse control. Importantly, the prefrontal cortex can exert top-down control over emotional responses generated by the amygdala and other limbic structures, allowing rational deliberation to modulate emotional impulses.

This prefrontal regulation of amygdala responses represents a critical mechanism through which individuals maintain deliberate behavioral control despite emotional activation. When prefrontal function is intact and engaged, the decision-making processes it supports can override amygdala-driven impulses toward eating, allowing individuals to choose behaviors that align with conscious intentions and goals rather than being purely driven by emotional state.

However, prefrontal function is resource-dependent and susceptible to impairment under various conditions. Fatigue, stress, alcohol consumption, sleep deprivation, and intense emotional arousal all can compromise prefrontal function, reducing its capacity to regulate amygdala-driven responses.

Dynamic Balance Under Different States

The relative influence of amygdala-driven impulses versus prefrontal control varies across psychological and physiological states. Under conditions promoting optimal prefrontal function—adequate sleep, low stress, positive emotional state—prefrontal control over amygdala responses is maximized. Deliberate decision-making can override emotional impulses toward eating.

Conversely, under conditions impairing prefrontal function—chronic stress, sleep deprivation, intense emotional arousal—the balance shifts toward greater influence of amygdala-driven responses. In these states, eating behavior becomes less dependent on deliberate decision-making and more driven by emotional impulses and automatic responses to food-associated cues.

This dynamic balance helps explain why individuals frequently report reduced capacity for food-related impulse control during stressful periods, after poor sleep, or during times of emotional distress. The neurobiological basis reflects not personal weakness but rather predictable changes in the balance between emotional and deliberate control systems.

Learned Associations and Emotional Conditioning

Through repeated pairings of food consumption with emotional regulation, amygdala-based learning mechanisms establish strong associations between particular foods and emotional states. Once these associations are formed, encountering the associated emotional state or environmental cues becomes capable of triggering amygdala activation and motivation toward the specific food, even in the absence of conscious recognition of this learned association.

This emotional conditioning operates largely outside conscious awareness. Individuals may not be consciously aware that their desire for particular foods reflects learned associations between those foods and emotional states. The amygdala's automatic responsiveness to learned associations means these motivated states arise without requiring deliberate thought or conscious recognition.

These learned associations can be remarkably persistent. Once established through repeated pairing of emotional state with food consumption, they can remain influential years or decades later, even if the individual is no longer consciously aware of their origins or has intentionally tried to modify food-related eating patterns.

Prefrontal Modulation of Conditioned Responses

While amygdala-based learning is relatively automatic and persistent, the prefrontal cortex maintains capacity to modulate responses to learned associations. Through processes termed prefrontal extinction learning, repeated exposure to learned cues without the associated outcome can lead to prefrontal-mediated inhibition of conditioned responses.

However, this prefrontal extinction learning requires resource allocation and active engagement of prefrontal cognitive processes. It is susceptible to disruption under stress—when stress impairs prefrontal function, previously extinguished conditioned responses can reemerge. This explains why individuals may show renewed food cravings during stressful periods even after periods of successful behavioral change.

The dynamic interplay between amygdala-driven conditioned responses and prefrontal-mediated regulation illustrates why emotional states so reliably influence food-related behavior. Stress, emotional arousal, and negative mood all impair the prefrontal function necessary to override amygdala-driven motivational states.

Neurobiological Basis of Emotional Eating

The interaction between amygdala and prefrontal cortex provides crucial neurobiological explanation for emotional eating. When emotional distress activates the amygdala, it generates motivation toward eating as an emotional regulation strategy, particularly in individuals with learned associations between emotional states and food consumption.

Simultaneously, the emotional arousal often impairs prefrontal function, reducing the capacity for deliberate decision-making that might otherwise override the amygdala-driven eating motivation. The combination—heightened amygdala-driven eating motivation plus reduced prefrontal control—creates powerful neurobiological conditions promoting emotional eating behavior.

This neurobiological framework illuminates why emotional eating typically occurs during periods of emotional intensity—the very conditions that maximize amygdala activation while simultaneously impairing prefrontal control represent optimal neurobiological circumstances for emotional eating to emerge.

Conclusion: Brain Systems in Food-Related Emotions

The amygdala-prefrontal interaction represents a fundamental neurobiological dynamic influencing emotion-related eating behavior. The amygdala's rapid, automatic responses to emotional stimuli and learned associations generate powerful motivational states. The prefrontal cortex's capacity for deliberate control and regulation provides counterbalance.

The balance between these systems shifts across emotional and physiological states. During stress, sleep deprivation, or emotional arousal, the relative influence of amygdala-driven responses increases while prefrontal regulation decreases. This dynamic helps explain the reliable observation that emotional intensity correlates with reduced deliberate control over eating behavior.

Understanding these neurobiological interactions provides foundation for appreciating the basis of emotion-driven eating in fundamental brain system dynamics rather than individual character or willpower.

Educational context: This article presents research on brain regions involved in emotional responses to food. It provides scientific information without offering personal recommendations or medical advice. Understanding these mechanisms supports informed appreciation of emotion-driven eating behavior.